Village

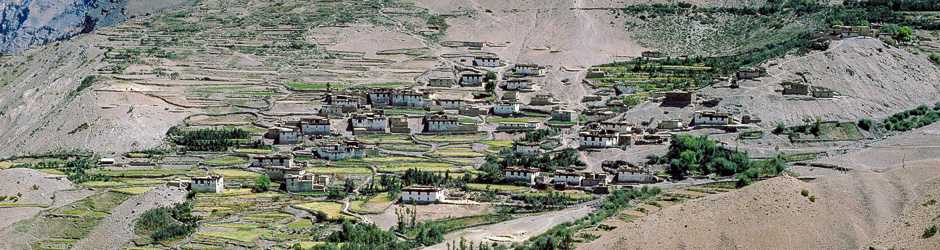

The picturesque village of Lalung (ལྷ་ལུང་; ◊ Lalung) lies to the north of the impressive village of Dankhar (བྲང་མཁར་), the former capital and seat of the Spiti ruler (Nono). Situated along a northern tributary of the Spiti river, the Lingti, Lalung is reached either after an hour’s walk from Dankhar, or via a link road branching off the Spiti main road shortly after Dankhar opposite the mouth of the Pin valley. Lying at an altitude of 3680 metres, Lalung is the only major village in the Lingti valley.

Both the ancient and modern temples are located on the hill to the right of the village. Lalung, too, must once have been a major Buddhist centre. There was once a large monastery on the flat hill-top above the village that probably occupied the whole of this site.

Today only two older temples remain on the hill. One is a tiny provisional chapel on the side of a house at the edge of the flat hill-top. I call this building the Vairocana Chapel, after the images it houses. The second site is the exceptional Serkhang (གསེར་ཁང་) or Golden Temple located on the crown of the hill. The relationship of the Serkhang to the Vairocana Chapel, which is approximately 35 metres WNW of the Serkhang, remains obscure.

Serkhang

The main room inside the larger structure of the Lalung Serkhang is also called Serkhang. It is only the latter room, measuring 5.65 by 5.2 metres and with a height of more than 4.5 metres, that is described here. This room is virtually packed with sculptures covering three walls in complex configurations. The entrance wall (west wall) has only two gate-keepers guarding the door (◊ Lalung Serkhang).

While the sculptures are largely original and well preserved, the painting on and around them is recent. Judging from the reports published, the whole temple was repainted at some point between 1926, the year that H. L. Shuttleworth and Joseph Gergan saw them, and 1933, when Tucci and Ghersi visited Lalung. While the repainting has not really affected the sculptures, the quality of the present murals is pitiful compared to the originals, which have only survived in a small section above the Founding Inscription to the left of the entrance. Nevertheless, the crude repainting appears to follow the original murals, which may still be preserved underneath. Some of its compositions can still be related to depictions found in the Alchi group of monuments, and also the iconography of the temple has its resonances there.

The organisation of the sculptural decoration of the temple is unique. In general, it follows an iconographic principle suggested by Rob Linrothe for the Alchi Sumtsek: Buddha on the main wall, Bodhisattva on the wall to his right (left-hand wall), goddess (or rather female Bodhisattva) at the wall to his left (right-hand wall), and protective deity on the entrance wall.

Buddha Śākyamuni on the main wall presides a three family configuration, with the Bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Vajrapāṇi placed in lofty pavilions at the top of the wall. At the level of his throne sit Brahmā and Indra in worship. The emphasised Bodhisattvas are complemented by three Bodhisattvas and two goddesses on each side, which have not been identified individually. A row of Buddhas complements the assembly along the bottom of the wall. All deities on this wall are surrounded by a common lotus scroll that emerges from a central vase composed of addorsed birds.

The left wall has a unique assembly presided by Mañjuśrī Ādibuddha, as also proposed in Tribe 2020. Presumably this is a core assembly of the Vajradhātu mandala specific to commentaries on the Litany of Names of Mañjuśrī (Mañjuśrīnāmasaṃgīti) that was complemented by the surrounding paintings. That many of the repainted Bodhisattvas hold a sword, supports this reading. Vertically the central Mañjuśrī is superseded by Mañjuśrī Jñānasattva (Tribe 2020), the four-faced figure holding two lotuses on top of the throne frame, and underneath is the four-faced Vairocana on the heart of which the above deities are visualised. Further, the paintings also feature an 11-headed and 22-armed Avalokiteśvara and Trailokyavijaya to the sides. In both cases, pairs of arms appear to have escaped the attention of the repainter. This new reading of this wall is confirmed by its detailed description in the Founding inscription (Tropper 2008, verses 47-68).

On the right wall is a mandala assembly dedicated to the goddess Prajñāpāramitā (Shérapkyi Paröltu Chinma, ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་མ་), who in this case is attributed to the family of Amitābha represented on top of her throne frame. She is surrounded by four Buddhas and four goddesses. This smaller assembly leaves considerable space for murals, with two large panels painted on each side. On the left are two teaching scenes or Buddha fields, on the right two rather distinct compositions. Of these the upper one may represent the Bodhisattva Dharmotgata's palace, with Prajñāpāramitā represented above him and the story of the Bodhisattva Sadāprarudita in search for the Perfection of Wisdom unfolding in the bottom area. The lower panel represents Green Tārā rescuing from the eight dangers, even though the depicted goddess is not green, and the Buddha above her is Akṣobhya and not Amoghasiddhi, as originally. Among the panels along the bottom the middle ones with the donors are most informative, as they compare well to Alchi. Given the context, it is unlikely that the representations of Padmasambhava and Yama Dharmarāja on this level were actually represented in the original program.

The entry wall is dominated by the protectors Vajrapāṇi and Hayagrīva flanking the entrance. They are accompanied by local protective goddesses which I tentatively identify as Mamo (ma mo) including the Peacock Cape Lady also depicted at Alchi. The three repainted mandalas are dedicated to Vajrasattva surrounded by the ten wrathful deities, Akṣobhya and Amitābha, the latter two aligning with the protectors underneath them.

The remains of the Founding Inscription to the left of the entrance have been spared the repainting but are poorly preserved. The seven syllable verse text of the inscription, now studied in detail by Kurt Tropper, does not provide secure historical information on the temple. The iconography of the temple and some of the motives reflected in the repainting indicate a date close to the Alchi group of monuments, and thus the second half of the 12th century.

Selected Literature

- Tribe, Anthony. 2020. Mañjuśrī as Ādibuddha: The Identity of an Eight-armed Form of Mañjuśrī Found in Early Western Himalayan Buddhist Art in the Light of Three Nāmasaṃgīti-Related Texts. In Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions. Essays in Honour of Alexis G.J.S. Sanderson, eds. Dominic Goodall, Shaman Hatley, Harunaga Isaacson, and Srilata Raman, 539-568. Brill.

- Tropper, Kurt. 2008. The Founding Inscription in the gSer khaṅ of Lalung (Spiti, Himachal Pradesh) Edition and Annotated Translation. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works & Archives.

- Luczanits, Christian. 2004. Buddhist Sculpture in Clay: Early Western Himalayan Art, late 10th to early 13th centuries. Chicago: Serindia: 89–106.

- Linrothe, Robert N. 1996. Mapping the Iconographic Programme of the Sumtsek. In Alchi. Ladakh’s hidden Buddhist sanctuary. The Sumtsek, eds. Roger Goepper, and Jaroslav Poncar, 269-272. London: Serindia.

- Tucci, Giuseppe. 1988. The Temples of Western Tibet and their Artistic Symbolism. Indo-Tibetica III.1: The Monasteries of Spiti and Kunavar. Śata-Piṭaka Series, vol. 350. ed. Lokesh Chandra. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Shuttleworth, H. Lee. 1929. Lha-luṅ Temple, Spyi-ti. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, No. 39. Calcutta.

The quotation below is an adapted translation of verses 60–62 of the Founding Inscription (Tropper 2008) the iconographic programme of the right wall making clear that Vairocana must be the Buddha referred to in the third line.

Vairocana Chapel

The chapel containing a four-fold image of Vairocana is today a crudely roofed structure attached to the side wall of a house. The room is 4.3 metres long and 3.1 metres wide. None of the surrounding architecture is ancient or provides any clues as to the original setting of the image. It seems that the four-fold Vairocana is the only remains of a temple once situated at the western end of the hill (◊ Vairocana). Only archaeological documentation and excavation would reveal the original context and function of the image.

In the Vairocana Chapel four similar images are seated on a single throne structure with their backs towards one another. That these four images are a representation of Vajradhātu-Vairocana can today only be concluded from a comparison with the four-fold Vairocana at Tabo. It is very likely that all the images once performed the teaching gesture (dharmacakramudrā) similar to the image at Tabo, but the gesture of highest awakening (bodhyagrīmudrā) also seems possible, as one image has its index finger raised. In any case, it can be assumed that all four images were once iconographically identical.